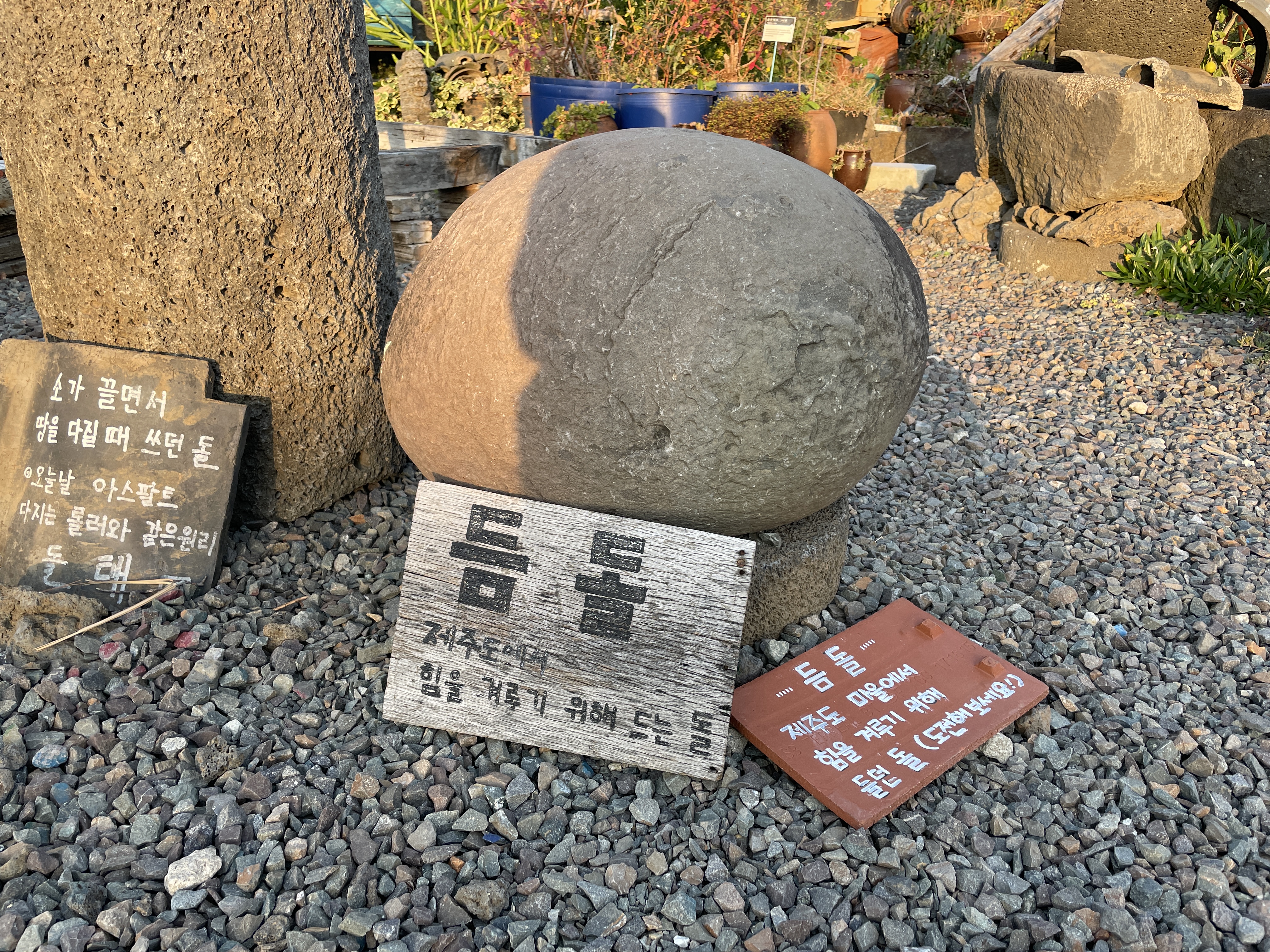

Jeju once had a widespread tradition of stonelifting. In the past, each village on the island had two to six lifting stones. These stones were placed at the entrances to villages and under shade trees for local youths to test their strength. Villages with heavier stones were afforded bragging rights, and residents made fun of the size of lifting stones in other villages.

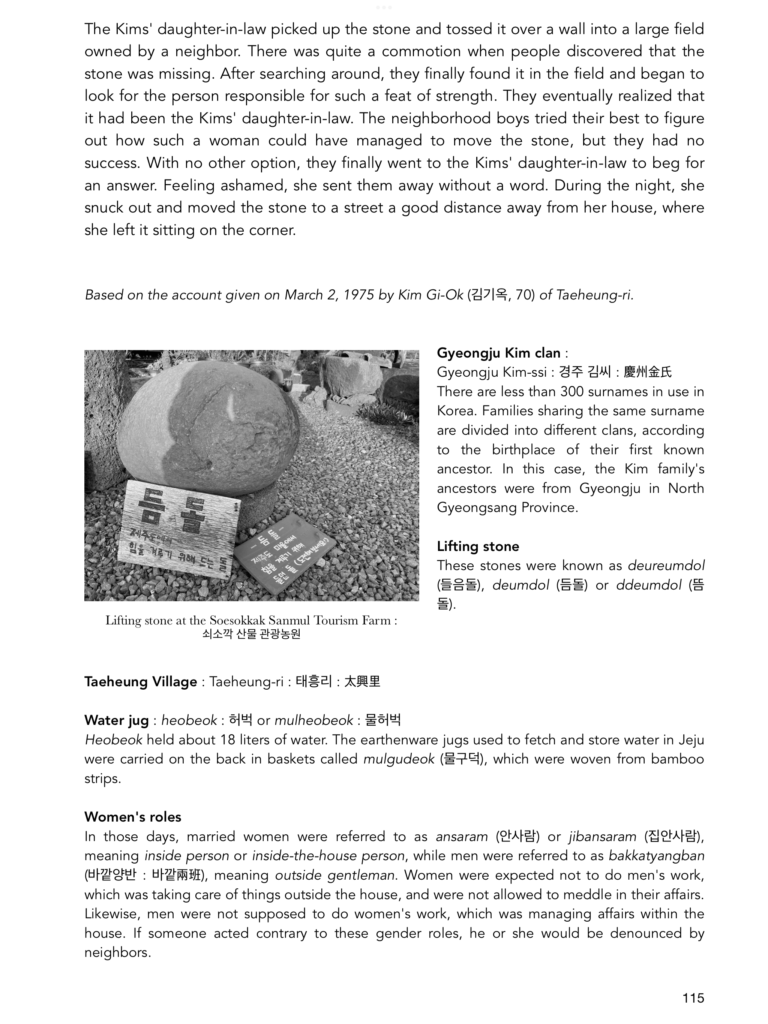

Lifting stones are known by a wide variety of names in Korea. They are commonly called deuldol (들돌) on the mainland, while in Jeju they are known as deumdol (듬돌), ddeumdol (뜸돌), deureumdol (들음돌), deungdol (등돌) or ddeungdol (뜽돌).

Landowners in Jeju used lifting stones to determine the strength of farm laborers, and thereby the wages offered. This practice also took place in Iceland and Sweden. Stonelifting also took place at festivals throughout the year. In modern-day Jeju, stonelifting was revived at the annual Fire Festival in early spring.

There were 6 levels involved in Jeju’s lifting stone competitions:

- Lifting the stone off the ground with two hands.

- Clutching the stone to your stomach.

- Straightening your back with the stone.

- Bringing the stone up to your chest.

- Taking a few steps while carrying the stone.

- Carrying the stone to a designated location in the village.

At “level 6”, the man was recognized as a true “jangsa” — “strong man”.

The residents of Siheung Village on the east coast used to be famed for their strength, and the village was formerly called Simdol (심돌 : 力石 or 力乭), which directly translates as “strength (or strong) stone”. The village’s website states that the village was first settled in the 16th century, and two reasons are given for the origin of the village’s name. One is that it referred to the strength of its inhabitants, who were generally stronger than people in other villages. The other comes from the fact that the area had many large stones that were firmly buried in the earth (sandol : 산돌) and thereby strongly resistant to attempts to remove them (when clearing the land for farming). There are a great number of legends from the village related to feats of strength.

Jeju’s stonelifting culture began to die out around the 1950s. Although many of Jeju’s lifting stones have disappeared, they can still be found in villages and museums across the island. Some stones are meant only for display, while others wait silently for the next man or woman to come along and test their strength.

I have been unable to find any sources that provide a comprehensive list of the locations of remaining stones. However, there are a handful of newspaper articles (in Korean) about particular stones. Taking trips to village offices, scouring village history books, and asking elderly residents of villages has proved successful in locating stones.

Check out liftingstones.org – a fantastic website dedicated to this ancient practice. The lifting stones I have been able to locate are now on the liftingstones.org map. Among the locations are the “Lifting Stone Street” in Hwabuk (화북) — where one can find several stones. Another is a guksu (국수 : noodle soup) restaurant in the village of Hallim called “Lifting Stone” (they happen to serve really good soup!). The owner’s grandfather placed a lifting stone onto the rock wall around the property, where it can be viewed today.

David Nemeth wrote a really interesting article on The Lifting Stones of Cheju Island (1984, Korean Culture – (Los Angeles)) Among his insightful observations are the following:

- The lifting-stone game can be interpreted at several levels. Superficially, and in the collective memory of most old folk, it was simply a contest of strength, a source of diversion and amusement: ‘Who’s the village champion? Well, let’s gather ’round the lifting stone and see!’

- Islanders deny … that they ever worshipped the stones. … Villagers agree that the stone-lifting game was a rite of passage for its young men. Competition with the stone was a strictly male prerogative.

- It is ironic and poetic that Cheju Islanders, faced with a lifetime of shifting heavy stones from fields to their margins and beyond, once lifted stones for fun.

- … if a stranger boldly entered a village he risked being invited to lift its stone. His failure could result in a thrashing at the hands of the locals, after which he could expect to buy for them a round of dlinks as recompense for his trespassing.

- Young farmers who while out in their fields felt helplessly out-numbered by entrenched armies of stone, could encircle a solitary liftingstone at the village center and enjoy the delicious reversal of roles they were enacting.

While Jeju has done an incredible job of documenting its tangible and intangible cultural heritage through the placement of information signs and the production of detailed books and documents, and the government has taken great care to protect and preserve its priceless cultural artifacts, lifting stones have yet to receive official status as protected aspects of the island’s cultural heritage. The reason for this is as of yet indiscernible, but perhaps a concerted effort to gain recognition for the value of lifting stones and the connection they provide to Jeju’s fascinating culture and history will provide fruitful in securing protection, before more of the stones are lost.

Jeju has a great number of variations of stonelifting stories, which were told all across the island. The following three stonelifting legends are extracts from my book 99 Legends of Jeju Island.